Scientists from South Korea’s Yonsei University have invented what they believe to be a sustainable, high-protein food in the form of “beef rice”, made by growing cow cells in grains of rice.

Tinged a pale pink from the cell culturing process, the hybrid food contains more protein and fat than standard rice while having a low carbon footprint, leading its creators to see it as a potential future meat alternative.

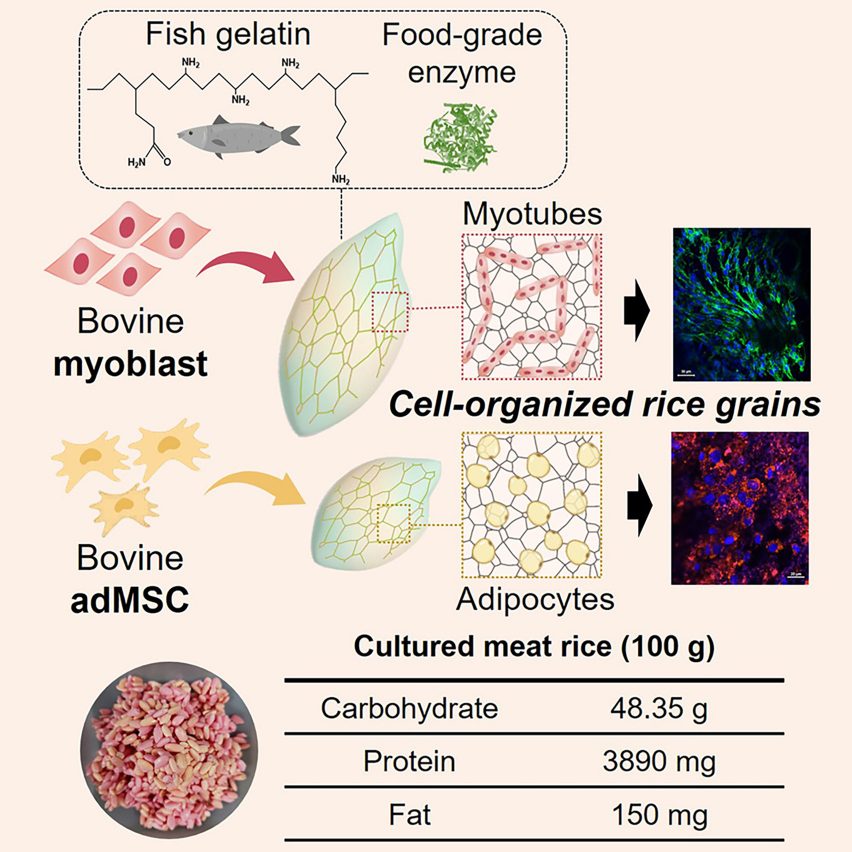

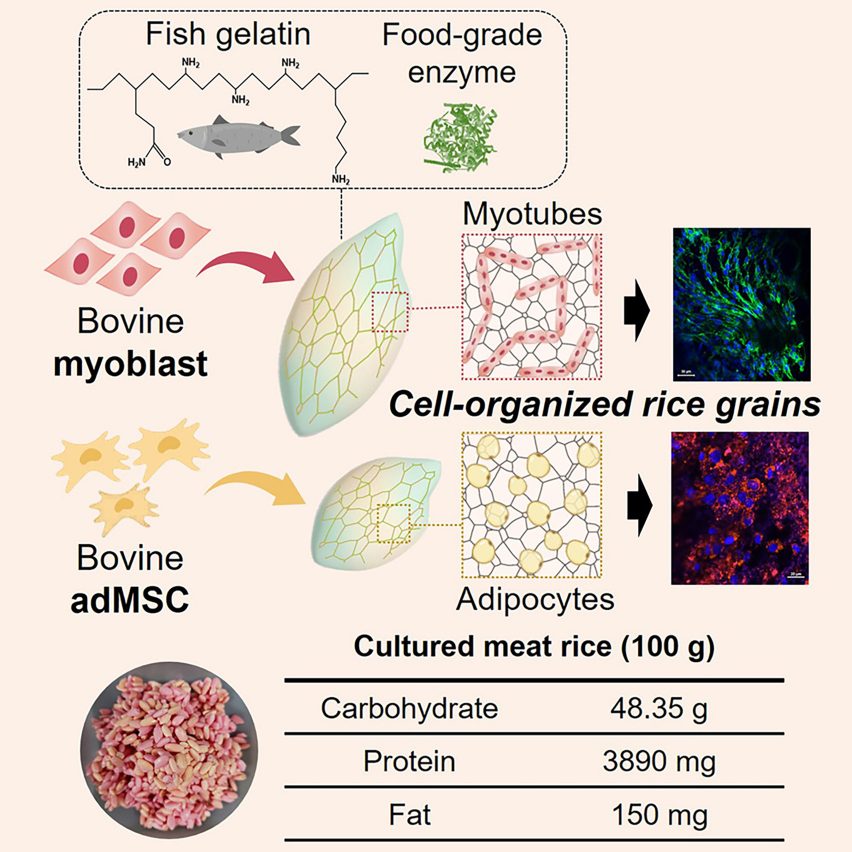

The beef rice was made by inserting muscle and fat stem cells from cows into grains of rice and leaving them to grow in a Petri dish.

Because the rice grains are porous and have a rich internal structure, the cells can grow there in a similar way to how they would within an animal. A coating of gelatine – in this case, fish-derived – further helps the cells to attach to the rice.

Although beef rice might sound like a form of genetically modified food, there is no altering of DNA in the plants or animals. Instead, this process constitutes a type of cell-cultured or lab-grown meat but with the beef grown inside rice.

In a paper published in the journal Matter, the Yonsei University researchers explain that their process is similar to that used to make a product already sold in Singapore – a cultured meat grown in soy-based textured vegetable protein (TVP).

Soy and nuts are the first foods that have been used for animal cell culturing, they say, but their usefulness is limited because they are common allergens and do not have as much cell-holding potential as rice.

The nutritional gains for their beef rice are also currently small, but the researchers from Yonsei University’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering say that with further optimisation, more cells and therefore more protein could be packed in.

The hybrid rice contains 3890 milligrams of protein and 150 milligrams of fat per 100 grams – just 310 milligrams more protein and 10 milligrams more fat than standard rice.

“Although hybrid rice grains still have a lower protein content than beef, advances in technology that can improve the cell capacity of rice grains will undoubtedly improve the nutritional content of hybrid rice,” the researchers said in their paper.

The scientists also believe the product could be inexpensively commercialised and tout the short time frame required to boost nutrition through culturing.

Whereas beef production usually takes one to three years and rice 95 to 250 days, they say their cell culturing process took less than 10 days.

“Imagine obtaining all the nutrients we need from cell-cultured protein rice,” said researcher Sohyeon Park. “I see a world of possibilities for this grain-based hybrid food. It could one day serve as food relief for famine, military ration or even space food.”

If commercialised, the hybrid grain is expected to have a low carbon footprint, similar to growing standard rice, because there would be no need to farm lots of animals. While the stem cells used for the process are extracted from live animals, they can proliferate indefinitely and don’t require animal slaughter.

An obstacle for some may be the taste; the cell culturing process slightly changes the texture and smell of the rice, making it more firm and brittle and introducing odour compounds related to beef, almonds, cream, butter and coconut oil.

However, lead researcher Jinkee Hong told the Guardian that the foodstuff tastes “pleasant and novel”.

The team is now planning to continue their research and work to boost the nutritional value of the hybrid rice by stimulating more cell growth.

Lab-grown and cultivated meats have been a subject of great interest and investment since 2013 when the world’s first lab-grown burger was eaten live at a press conference.

However, scaling up production, clearing regulatory hurdles and creating an appealing taste and texture have proven a challenge, and there are few examples on sale anywhere in the world.

In the meantime, speculative designers have explored the issue. Leyu Li recently created three conceptual products that, similar to beef rice, combine lab-grown meat with vegetables, calling them Broccopork, Mushchicken and Peaf.

All images courtesy of Yonsei University.